I was guided through Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House in Los Angeles by a man who in his childhood lived near Oak Park, Illinois, where many of Wright’s early structures were built.

I was guided through Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House in Los Angeles by a man who in his childhood lived near Oak Park, Illinois, where many of Wright’s early structures were built.

That man, Henry Michel, writes in the forward of his self-published book “Basic Frank Lloyd Wright” (1999) that he is an “expert amateur” who has written two other books on Wright’s work.

Whether fact or fiction, Michel’s tour of Hollyhock House and his tale of Aline Barnsdall, the theatre producer who financed it, was memorable. He hustled through the gardens and rooms chastising tourists who lingered too long or peered into off-limit areas.

I was travelling alone. The others on the tour were similar to those I’ve seen at other Wright sites: mainly down-to-earth American enthusiasts in untucked shirts, shorts, tube socks and sneakers.

There were a couple of architects who childishly violated all of Michel’s rules by waiting until he had marched off to the next gathering point before darting up forbidden stairways or surreptitiously snapping pictures.

Although I wasn’t compelled to join them in their anarchist acts, I understood their need to see and capture all the desolate magic of that crumbling place.

Each of the 12 Wright sites I’ve visited since 2002 has a very distinctive flavor beyond the expected architectural idiosyncrasies.

UTOPIAN IDEALS

When Wright proclaimed a Declaration of Independence from architectural tradition in 1896, he was articulating the utopian vision that would inform his work throughout his career.

Wright’s declaration proposed a political and aesthetic ideology geared toward developing a style of architecture he hoped would transform and improve U.S. society.

A central tenet of Wright’s philosophy was that traditional European architecture contained irrelevant ornamental design elements that should be set aside, or reinterpreted, to generate a more organic architecture.

Wright’s ideas for a new style of architecture emerged under the influence of technological changes that were transforming the U.S. into an industrialized and urban society at the turn of the last century. Wright was also influenced by creative European movements such as the Arts and Crafts and International Style.

About half of the 1,000 buildings he designed between 1887 and 1959 were constructed throughout the U.S., Canada and Japan, according to Arlene Sanderson’s “Wright Sites” (Princeton, 2001).

Wright believed there was a need to create an architecture unique to the U.S. that would serve to enhance humanity in its surrounding landscape.

He opposed the use of ornament found in traditional architecture exported from Europe to the U.S.—terming it degenerate—and spent his career in pursuit of what he called organic architecture.

In “An Organic Architecture” (1939), Wright said he wanted to meld together form, structure and space in such a way as to create complete entities he believed would transform and uplift society in a manner suited to the liberal idealism he perceived as characteristic of the U.S.

He sought to create structures that would be unified with their surrounding landscape and to incorporate ornamentation into overall design so that they would become enclosed organisms.

DEPARTURE FROM TRADITION

As Wright eschewed what he called the false purpose of traditional ornament, he reinterpreted it. He believed his methods would improve the human condition at large.

In “An Organic Architecture”, Wright commented on Michelangelo’s dome on St. Peter’s Basilica (1506-1615) in Rome and Christopher Wren’s copycat dome on St. Paul’s Cathedral (1675-1708) in London expressing his belief that traditional architectural ornament serves only to lend a form of false authority to a given structure.

“I declare, the time is here for architecture to recognize its own nature, to realize the fact that it is out of life itself for life as it is now lived, a humane and therefore an intensely human thing; it must again become the most human of all the expressions of human nature,” he wrote.

“The ‘Classic’ [architecture] was more a mask for life to wear than an expression of life itself … Modern architecture—let us now say organic architecture—is a natural architecture—the architecture of nature, for Nature.”

Wright’s efforts to use exterior ornament solely for a functional purpose and to mesh with the natural landscape are reflected in his Prairie period in the early part of the 20th century.

The Prairie houses are built of natural materials and have low roofs and stained-glass windows. They are also characterized by a central garden. The surrounding home creates an enclosure around the garden, which establishes an organic core—a rustic predecessor to Wright’s more streamlined futurist work.

Wright’s later tendency toward designing sleek, science-fiction like, self-contained organic entities emerges in his Usonian period of the 1930s. His utopian aspirations led him to design such futuristic buildings as the Marin County Civic Center and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1956). In those buildings ornamentation becomes formalized as a part of the overall structure.

ENCOUNTERING WRIGHT

In 2002, I drove from Madison, Wisconsin, to Taliesin (rebuilt 1925) in Spring Green where Wright lived. I toured the Hillside Studio and theatre. Hooked, I returned the next day to tour the house. There was no admission charge to visit the church and cemetery where Wright is buried, but the cost to tour the other buildings was very high.

On that trip I also saw Monona Terrace (1995, based on 1959 design) in Madison.

When I returned to Madison in June 2006, for a wedding, I stayed at the Monona Terrace Hilton so I could overlook the terrace and the lake. It serves as a giant piazza for Madison residents.

The uncle of my newlywed friends took me on a tour of the Unitarian Meeting House (1947), which was free to the public.

He drove me to the Gilmore House (1908) but it is privately owned and we couldn’t go inside.

En route to Madison from Milwaukee by car last year, I made a special trip to the S.C. Johnson Administration Building (1936) in Racine. I got lost several times on the way because I took local roads in order to avoid the major highway. I wanted to drive next to the lake.

There was no charge for the tour of the Johnson building, but visitors have to book ahead. Photography is banned on the grounds and there is an obligatory 20-minute promotional talk on S.C. Johnson’s company history and cleaning products.

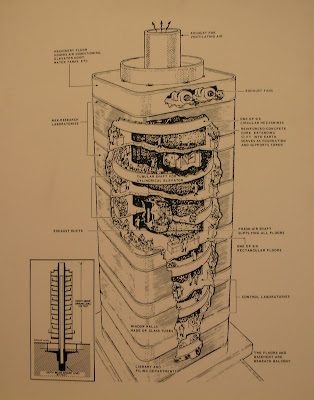

The so-called Great Workroom, with its ingenious upside-down inverted mushroom-like pillars is still in use, so visitors are corralled in a specific area of the room. The research tower is off limits. It is used for storage because it doesn’t meet modern-day safety standards. If you click on the diagram below you can see the detail.

On the drive back from Madison I got lost trying to find the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church (1956) in Milwaukee.

I found myself trapped in a dystopian suburban network of roads driving in circles or figure eights for about an hour. I am not sure if my map was outdated. There were no human beings.

It was more frustrating than driving down the curvy Pacific Coast Highway from San Francisco to Los Angeles by myself in September 2005, but not as scary. That was a white-knuckle drive.

The Greek Orthodox Church does not allow visitors inside unless there are 15 people all clamoring to get in at once so I sated my curiosity by peering in windows and wandering around outside.

While in California I visited the aforementioned Hollyhock House in Hollywood.

I took the ferry to San Rafael from San Francisco, past San Quentin State Prison, to see the Marin County Civic Center (1957). There was no official tour and visitors can go anywhere they like both inside and outside the building. It is truly spectacular. Some of the furniture was made by San Quentin inmates.

In San Francisco, I went to the V.C. Morris Gift Shop (1948). It has an interior spiral slope which is a sort of mini version of the one in the Guggenheim. It’s an African artifacts gallery and bookshop.

In 2002, I made a journey by Greyhound bus from Toronto to Madison making stopovers in Detroit and Chicago to see art, architecture and baseball. While in Chicago, I took two walking tours. In the morning I saw historic architecture and in the afternoon modern architecture. The Rookery Building foyer (1905) which Wright remodelled, was on the tour.

I visited the Guggenheim Museum in spring 2006, when I was in New York. I’d been there before, but not when David Smith’s sculptures were on show. They provided suitable ornamentation for the giant swirling ramp, which is the focal point of the museum.

Unlike Henry Michel, I can’t claim even to be an “expert amateur” when it comes to Wright and his work, but I am deeply addicted to his buildings. Next, I plan to see Mill Run (1935-1948) in Pennsylvania, which is said to be Wright’s organic masterpiece because it is built over a waterfall ~

Pictures to come of the other sites once I’ve scanned them.