Annie Lennox, Bianca Jagger and Helen Pankhurst on London’s Millennium Bridge on International Women’s Day 2011. Picture: Julie Mollins

My first introduction to Britain’s Pankhurst family came during a screening of “Mary Poppins”, a 1964 film set in Edwardian England about a magical nanny tending to the children of an activist involved in the fight for women’s suffrage.

The lyrics of the “Sister Suffragette” song in the film make mention of “Mrs Pankhurst” being “clapped in irons again” for her part in the militant activities that in 1918 won women over the age of 30 the right to vote — a right revised 10 years later to grant suffrage to all women in Britain over the age of 21.

Although the struggle — which led to various imprisonments for Emmeline Pankhurst, her daughters Christabel and Sylvia, and members of the Women’s Social and Political Union she founded — ended two weeks before her death in 1928 at age 69, her great-granddaughter, Helen Pankhurst, carries on the fight for women’s equality.

“My view is that political participation and women’s representation issues are incredibly important, and women’s leadership still needs to be campaigned for — we have massive inequalities,” said Pankhurst when I first spoke with her in 2012 at a World Toilet Day event in London, organised to highlight the fact that globally 2.5 billion people do not have access to adequate sanitation.

This year on International Women’s Day, Pankhurst, who is currently undergoing chemotherapy treatments for cancer, will march as “Walk in Her Shoes” ambassador with charity Care International, in solidarity with women and girls in the developing world who often walk for up to six hours a day to fetch water. The International Women’s Day event on March 8, marks the launch of a fundraising campaign encouraging people to walk 10,000 steps a day for a week.

“Water collection is something that young women and girls, older women, pregnant women, sick women, elderly women, women with cancer deal with every day in very difficult conditions — we’re walking with that image in mind,” Pankhurst said during an interview on Friday.

“International Women’s Day is a fantastic moment when you can bring forth both the positive ideas about what has been achieved and highlight some of the areas that still need action.”

In Africa, about 90 percent of the work of gathering water and wood for the household and for food preparation is done by women, according to U.N. Water, suggesting that providing access to clean water can reduce women’s workloads and free up time for other economic activities, including education.

The Walk in Her Shoes march, which will leave from Tate Britain art gallery on Millbank, where an exhibition of Sylvia’s artwork depicting early 20th-century working conditions for women is on display until March 23, will wend its way to Festival Hall on the South Bank.

We dress as suffragettes to bridge the symbolic gap between women’s experiences in Britain — remembering our own ancestors and how people lived not that long ago, not having their toilets in the main house, having to collect water — it’s not in living memory, but almost, and it’s a reality for women in developing countries now, said Ethiopian-born Pankhurst, the granddaughter of Sylvia.

After the march, Pankhurst, who has worked with charity WaterAid, Womankind and the Agency for Cooperation and Research in Development will participate in a panel discussion about women, water and sanitation hosted by the Women of the World Festival.

She spoke with me via Skype:

Q: Why should people care that women have to carry water for household use?

A: I think it’s unacceptable that we can live in a world that’s so interconnected in so many ways and yet this basic daily drudgery that limits capabilities, potential, and all sorts of other things can be allowed to continue. It’s something that we can do something about. We can change things. To me, it’s just appalling that we continue live in a world where some people have several taps, lots and lots of taps nearby, and others have to go for a two-hour walk in the cold or in the beating sun to get 20 litres of water, which they have to make use of for all their needs.

Linked to that is also the sanitation and hygiene issue. If you don’t have enough water, then sanitation and hygiene is difficult — often the two come side by side — so you have communities, which have no access to water and also have no access to sanitation. If you don’t have sanitation then there are all sorts of issues around security and dignity and with girls and school — if they don’t have latrines, they don’t go to school, then they miss out.

Q: Can you draw a line from when your great-grandmother was fighting for women’s rights and the situation today in the developing world?

A: I think some of the conditions are similar — and attitudes towards female domestic labour that have changed to a good degree in developed countries still remain very biased. Women are responsible for domestic chores in many developing countries, they aren’t the head of households in any shape or form and have to fulfill subservient roles. Unless these issues are addressed in the home, at the kernel of domestic life, then nothing else changes. For me, it’s incredibly important because it effects so many — it’s such a daily experience and because without it, you can’t capitalise on potential and change.

Q: In some countries, women seem to face insurmountable challenges complicated by the threat of violence. What is the solution?

A: Violence against women in all its forms is generic to all cultures and all places in the world and that’s a major, major barrier to change . . . If you don’t have power then you are exposed to violence and then as soon as you have power and a voice it’s less likely to happen. The question is, how does one speak out and ensure protective laws are there and applied? And how do we ensure rules change to stop all of that — from the petty little side comment through to rape — the greatest abuse that there is? I’m noticing a bit of a split in that I think. Put simply, in countries where individual women manage to raise their voice and put groups together to make a noise, things start to change more rapidly. In many countries, social media have really played a pivotal role in starting to change things in creating a voice that women can use. There’s the Everyday Sexism campaign in the UK started by Laura Bates tweeting abuse she’d been hearing that was picked up by other people.

In India, there has been a big response to rape, with people vocalising a “this cannot continue” type of statement. I think the more that happens, the more we have this bubbling up of a voice that says: “No, just because this has happened in the past it doesn’t mean to say we’ll continue to tolerate it. Just no.” The more people that can say no, collectively, loudly, I think the more things will change. That’s not to say that there aren’t incredible traditional powers and forces that continue to stamp us down. There are two I would particularly highlight, one is the pornography industry and the power and dissemination it has and the other is the military, the violence through war that perpetuates ideas and stereotypes by which women are subordinated and subjected to violence.

Q: What about the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals debate and discussion? It seems there might be a gender-specific target among the goals being discussed to replace the Millennium Development Goals when they expire. Do you think that has any effect or potential?

A: Yes I do, a standalone goal around women’s empowerment up front would be fantastic. I think symbolically it’s incredibly important. It shows commitment and can be used by activists who call governments to account and monitor change to ensure funding, so I think it has a very important role to play.

Q: Why do you think some women are afraid of the word “feminist”?

A: My instinct is that more and more women are actually really comfortable with that term and much more politically active . . . in the form of social politics. It used to be men interviewing me, men as photographers, men choosing whether the piece would be run and the whole system was just men. Gradually, it’s been infiltrated and now, although the photographers are still by-and-large men, the journalists are increasingly women, people who are commissioning the pieces are increasingly women and there is a groundswell. It’s still tough, it’s still not what we would want it to be, but I do feel a sense that the world is only going to be better for all of us — men and women — if we address some of these incapacitating constraints . . . It’s just changing a narrow mindset — if we all embrace diversity and allow ourselves to be the best that we can, all of us benefit.

Q: In these times of economic hardship, it’s difficult not to see women sliding backwards in relation to men. Do you think this is having a negative affect on women?

A: I think a lot of statistics show that the burden is affecting women in many ways. They are often easiest to cut in the labour force, often being in nationalised rather than private-sector work. Childcare and care for the elderly is being cut and women tend to have all those burdens put back on their shoulders. I think that it’s a dangerous time in terms of some of this slide-back economically. However, I do also think that there are trends that are working in the other direction, such as increasingly, girls education and employment opportunities being very good because women work hard and they work well and employers like to employ them. It’s a difficult time no doubt because of those pressures and I don’t want to minimise them, but I also don’t want to get so depressed about them that we give up.

Q: Are there any particular stories that stand out, or is there any particular image you have of your great-grandmother Emmeline and grandmother Sylvia that stand out for you?

A: What’s interesting for me about my family background is that they ended up with very different political views in terms of party politics . . . Emmeline and Christabel became very conservative, and Sylvia was very, very left wing. For me, that’s always been interesting because I like the idea of cutting across narrow political boundaries and I think it’s important that women work across whatever divides there are in our different societies and cultures. I think they shared different views, but I quite like the idea that feminism can be a term that anybody can use regardless of what political position they hold, regardless of whether they are a left winger or right winger, regardless of whether they are male or female, regardless of what class they are, regardless of what caste they are. It’s a unifying term. We can achieve more, rather than always have our political-making machinery, our decisions, our thoughts, bounded by these other schisms.

Q: Apart from your birthright, how did you become a feminist?

A: I was brought up in Ethiopia and I think seeing some of the difficulties of girls and women — learning about early marriage, forced marriage, and just by osmosis I saw what that must be like. And then in the UK as well, all these things about names, women changing their names when they get married, children taking the names of their fathers, not of their mothers. As a young girl you’re commented on based on what you look like, not what you say — all these superimposed factors influenced me more than any particular document I read. I think definitely the fact that people used to ask me about suffragettes, so I had to know about it. I’d ask questions and read up on it and develop my own understanding, but I think it came from both observation of what the world was still like and books more generally.

To join Helen Pankhurst, her daughter Laura and the Olympic suffragettes on International Women’s Day, visit: www.careinternational.org.uk/IWD2014

To sign up for the wider Walk In Her shoes campaign, walking 10,000 steps a day for a week in March, visit: http://www.careinternational.org.uk/walkinhershoes

Follow Helen Pankhurst on Twitter

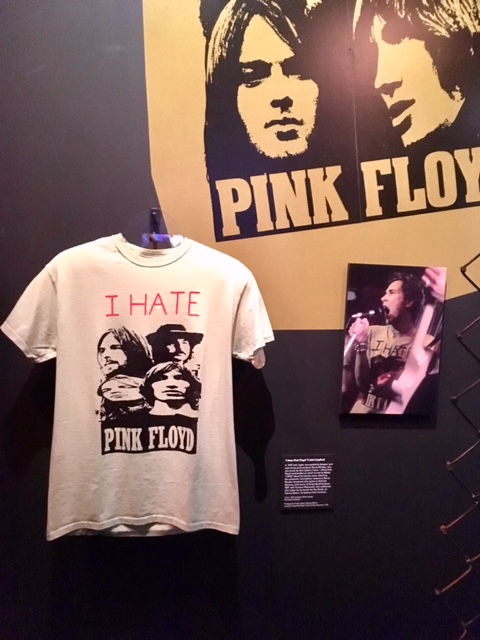

The Pink Floyd exhibit on show at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London is not for the myopic.

The Pink Floyd exhibit on show at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London is not for the myopic.

There is very little chronologically presented information to help visitors understand the context of the exhibit. I saw no basic timelines or biographical information about the band or band members. Inexplicably, current event news presumably placed to accompany different album releases, is displayed in the classic red British telephone boxes designed by Giles Gilbert Scott. However, tiny headlines and dates on publications are also often impossible to read.

There is very little chronologically presented information to help visitors understand the context of the exhibit. I saw no basic timelines or biographical information about the band or band members. Inexplicably, current event news presumably placed to accompany different album releases, is displayed in the classic red British telephone boxes designed by Giles Gilbert Scott. However, tiny headlines and dates on publications are also often impossible to read. After an hour and a half spent roaming around trying to make sense of things — my friend and I beat a hasty retreat once we came upon the sit in — we found ourselves in a gift shop packed with Pink Floyd items on sale.

After an hour and a half spent roaming around trying to make sense of things — my friend and I beat a hasty retreat once we came upon the sit in — we found ourselves in a gift shop packed with Pink Floyd items on sale.