An exhibition featuring the work of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera currently on show at Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario

(AGO) would have sparked heated debate in the late 20th century, but in today’s post-feminist world the pairing sidesteps controversy altogether.

In the past, celebrating a woman artist side-by-side with her husband would have been seen by feminists as a sign of her oppression by the patriarchy. However, traditional feminist debate about women artists, which has historically centred on a fight for individual recognition in a male-dominated art world — so common in decades gone by — is not mentioned in the AGO show or in the exhibition catalogue.

Instead, curator Dot Tuer inverts the tradition that would have cast Kahlo in Rivera’s shadow and celebrates Kahlo’s artistic abilities, proposing that the powerful feminine themes of her work have eclipsed the outmoded activist bent of Rivera’s.

Rivera reached international renown as a communist mural painter in the 1920s, depicting the Mexican revolution and class struggle, while Kahlo — 20 years his junior — was at the time more modestly acclaimed by the surrealist movement and the Mexican art world for works focused on her own personal suffering.

“Rivera no longer looms larger-than-life in the public imagination as Mexico’s greatest muralist accompanied by a much younger and diminutive wife,” Tuer says in the exhibition catalogue. “Instead, Frida is seen as the iconic artist with Diego cast in a minor role as her much older and philandering husband.

“Numerous exhibitions have enshrined her as one of modernism’s most profound women artists, whose self-portraits embody both the physical suffering she endured after a debilitating bus accident and the spiritual anguish caused by Rivera’s infidelity and her inability to have children.”

Rivera’s reputation declined during the Cold War and with the rise of abstract expressionism, Tuer writes, his work now dismissed as cartoonish political propaganda, despite major retrospectives in Mexico City, London and Detroit since the mid-1980s.

These supportive claims for Kahlo’s work must surely mark sweet victory for such feminist art critics as Lucy Lippard, Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock who struggled in the latter part of the 20th century to stake a place for forgotten women artists on gallery walls in the world’s major art collections.

Also for such artists as Judy Chicago who sought to generate valid “herstory” through her internationally recognised “Dinner Party” and “Birth Project” art exhibitions of the 1970s and 1980s.

The installations, which featured ceramic plates and tapestries, named women whose importance Chicago said had been largely written out of history. She argued that craft — typically ghettoized along with artistic women — should be considered art and that art made by women should be taken seriously by the establishment.

Such universal concerns led eventually to the creation of a women’s art museum in Washington, D.C., which opened in 1987.

“By its very existence, the National Museum of Women in the Arts challenges the unequal representation of female artists in other museums, in galleries, and in major shows and offers an important and national alternative space,” wrote art historian Alessandra Comini in the 1987 museum catalogue.

Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics and Painting, which closes at the AGO on Jan. 20, 2013, before re-opening at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art on Feb. 14, offers an unapologetic perspective on Kahlo as an equal with her husband, not as a victim toiling in his shadow.

More than 80 drawings and paintings, accompanied by photographs of the couple show how their lives were intertwined, despite troubles that led to their divorce and remarriage.

Not long before Kahlo died in 1954 at age 47, she referred to Rivera as “my child, my son, my mother, my father, my husband, my everything.”

Rivera referred to Kahlo’s death as the most tragic day of his life.

“Too late now I realised that the most wonderful part of my life had been my love for Frida,” he said.

Picture credit: Hospital Henry Ford, 1932, oil on metal, from the

Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico. Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society, New York.

________________________________________

Addendum

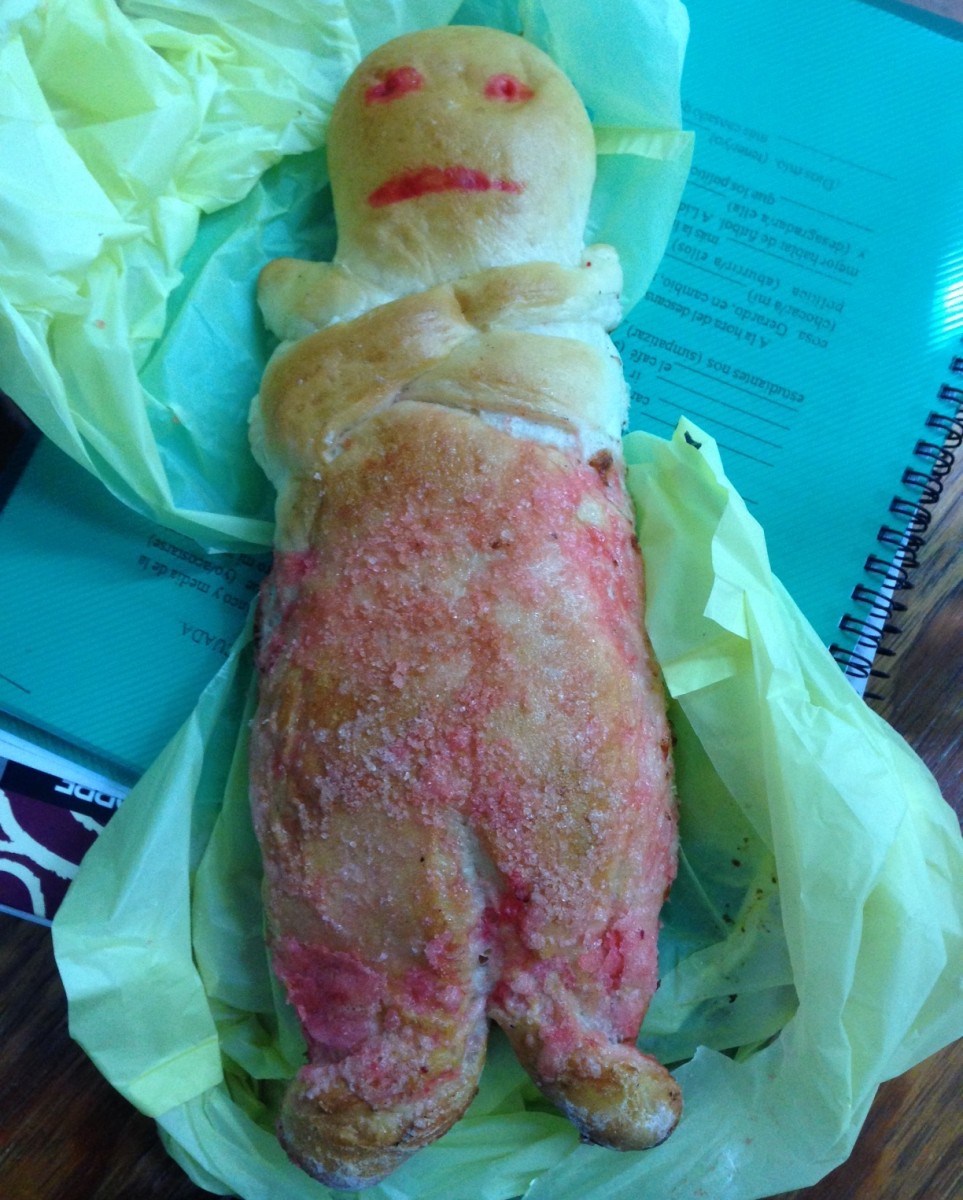

I painted this plaster cast, a copy of one Kahlo wore and painted, for a production of a 1994 play titled “Frida K” produced at the Toronto Fringe Festival.