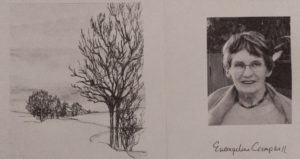

Two weeks ago on April 28, I attended a memorial for Evangeline Campbell (1934-2018), also known as “Vange” and even “Mrs Campbell” in days gone by when children addressed their elders with respectful titles.

Two weeks ago on April 28, I attended a memorial for Evangeline Campbell (1934-2018), also known as “Vange” and even “Mrs Campbell” in days gone by when children addressed their elders with respectful titles.

On the eve of Mother’s Day, I’m thinking of her. She is in my thoughts not only as the mother of Rebecca and Naomi — friends I’ve had the good fortune to have known for 80 percent of my lifetime — but also as a friend.

At Evangeline’s memorial, which took place in the upstairs space at the Great Canadian Theatre Company in Ottawa, I was struck by the eulogies. They mostly centered around letters — letters she had written, letters others had written to her and unwritten letters. As I listened, I thought about how she had penned and openly voiced her struggle with writing them — as I have — and as probably all letter writers have done at times.

But what struck me most of all was how many letters she had written and what a big impact they obviously imprinted on the lives of her friends. This got me thinking, and today I took the letters I had received from her out of a box to re-read them.

She wrote to me mostly over the five year period when I lived in London from 2008 to 2013.

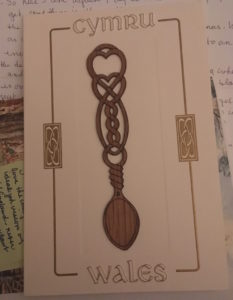

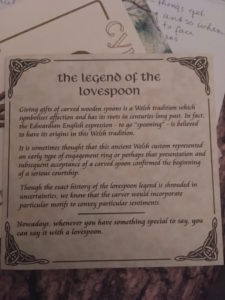

The letters are packed with information — written in neat longhand, often on multiple cards on different dates, but placed in a single envelope to send overseas. Some include Post-It notes and in one, two small gifts: a hankie and a welsh spoon — for me, a reminder of a long ago stay and family walk at Buck Farm near Wrexham, Wales on her recommendation.

Keepsakes within keepsakes, thoughts on thoughts, as well as caring concern and aesthetic ruminations on art, textiles, literature and imagery.

She was an artist. She was dissuaded from art school into a university library science program to study for a career. A similar fate of so many artists it would seem, but in fact putting her into an avant-garde of Canadian women who were university educated, married career women, with children.

Her career and a job with the federal environment ministry took her to Washington for conferences a few times, and she stayed at our home in Georgetown after they were over, enjoying art and culture. Highlights included a Shirley Horn concert, music at Blues Alley, One Step Down, visits to Dumbarton Oaks, textile and other museums — once with her husband Douglas — and always with my parents.

In 2013, I moved from London to live in Bogor, Indonesia. She thoughtfully rang me when I was visiting Toronto for Christmas to wish me good fortune before I returned to Bogor.

The last time I saw her, she took as a gift one of the pussy hats my mother and I had knitted for the Jan. 21, 2017 Women’s March (on Washington) to protest President Trump’s derogatory anti-women remarks.

On March 18, two months after the march, Evangeline, Douglas and Rebecca visited for lunch and she left wearing the hat.

Almost 10 years earlier, in 2007, she had written in a card after a visit to our home in Toronto that she wished she could have made her way around the living room to examine the pictures more closely.

She and I were both born when the sun was in the sign of Taurus — a few days and quite a few years apart. I tried to remember to write to her on her birthday each year from Indonesia and later Mexico where I moved in 2014 — countries with unreliable postal services — by email, but there were gaps.

I found a descriptive and tedious email I sent last year when I was in Nairobi attending a conference on the fall armyworm pest. Not exactly the kind of note one wants to receive on their birthday, I thought in retrospect.

At the conclusion of the memorial, friends were told they could take letters and cards addressed to them that she had started writing and which were left unfinished.

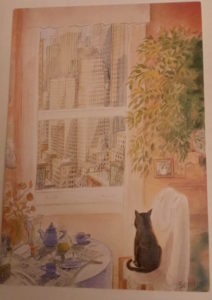

There was another box of blank cards and I took several. I am quite sure she would have been likely to send me the card pictured on the left featuring a cat peering out a window at a cityscape from a chair, a representation of “Neuf heures de matin,” by Jean- Jacques Sempe.

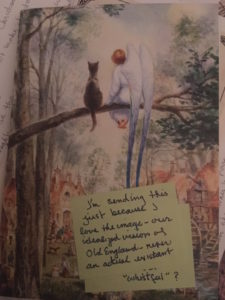

Compare it with “Summer Peace,” on the right, featuring a cat and an angel on a branch, a reproduction of a watercolour by Vladimir Rumyantsev, she sent to me in 2011 because she loved the image: “Our idealized image of old England,” which never actually existed, she wrote.

I’m not sure who will receive the cards I selected, since letter writing is now almost a thing of the past.

This at least is certain, fond memories of pleasant times will prevail.

***