This story was originally published in May 2006, after a visit to Cuba with my sister Tracey. I’m republishing it now in memoriam. Former President of Cuba Fidel Castro died yesterday.

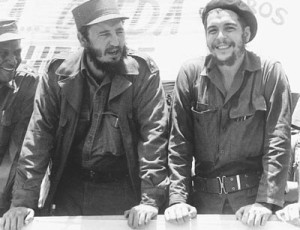

Handout picture shows Fidel Castro and Che Guevara

Our father taught us to respect Castro and the Cuban revolution because it aimed to help people. We learned about the contradictory relations between Cuba and the United States. Contradictions I observed first hand and wrote about in a story published in Canadian Business magazine under a pseudonym. I penned it under my maternal great grandmother’s name, Agnes Arundel Kyte. That story, “Our brands in Havana: What embargo? U.S. to Cuba trading is thriving,” like the following blog post was also published in May 2006.

Witness to Cuba’s ongoing revolution

HAVANA

HAVANA

On February 21, 2006, I returned from a week in post-apocalyptic Havana where I distributed 100 pencils and erasers.

People told me to take all kinds of items as gifts for the people of Cuba before I left Canada, but I didn’t know what to take or how to distribute it. So I winged it.

Most of the pencil distribution went smoothly, but on one occasion I was mobbed by a group of about 10 children who snatched at the pencils and broke some of them. After the mayhem, a few of them trailed after me along the sidewalk complaining that their pencils were broken or that they didn’t have an eraser. There was nothing I could do about it as I carried limited pencil reserves in my purse at a time.

I also distributed packages of gum, coloured pencils and pencil sharpeners.

I gave out lots of my own possessions because many people asked for various items. On one occasion a man in a shop asked me for my baseball cap. I agreed to give it to him, but told him I needed a cap in exchange.

He rustled around in a bag of hats and handed me a military green one with a picture of Che Guevara above the peak. He asked for five pesos. I agreed to pay because I found it hard to refuse, but it wasn’t fair trade. I bought many crafts from him at the asking price and when I left the shop he kissed me on both cheeks.

That was a University of Toronto cap.

I gave a Toronto Blue Jays cap to a beggar wandering just outside Plaza Vieja holding a card written in English which said he is mute. When I didn’t give him money he touched the cap, which was hanging off my bag, and indicated he wanted it.

A lot of people were very grateful for the pencils and said they would give them to their children. Many people asked for pens, but I only had a few.

THE HOTEL AND NEIGHBOURHOOD

The accommodations at Hotel Los Frailes were very good and quiet. The atmosphere is Gothic. The employees wear mock monk vestments, which are made of soft burlap with a simple cord around the waist. A life-size statue of an iron monk with no head stands outside the main entrance of the hotel.

The hotel room key had a fake old-fashioned oversized key attached with the room number in huge font imprinted on a round metal disk.

Los Frailes is centrally located and right near one of the nicest plazas in Old Havana. The Plaza Vieja is currently undergoing renovations to return it to former glory, but much of the work is complete. One restaurant on the square, Taberna de la Muralla, brews its own beer and sells it by the pint for 2 pesos, another, El Portal del Santo Angel, serves top-notch mojitos for 2 pesos.

The Camera Oscura building on Plaza Vieja shows vibrant images of the entire city on a concave white circle in a rooftop room.

Plaza San Francisco is also nearby. It has a taxi stand on it. Much of Old Havana is pedestrian only, which means it is very convenient to stay relatively near a motorway for easy access to other parts of the city.

Cafe Mercurio, which is on the square, is a very good place to go for breakfast. The staff is very friendly and it has a nice outdoor patio guarded by a woman who wears her hair in a turban, wields a broom and supervises a pack of wild dogs.

The core of the city–Old Havana–is in fairly presentable shape as the buildings have been renovated to aid in attracting tourists to the city. Time seems to have stood still and much of the rest of the city has collapsed or is collapsing. Some people are living in buildings supported by wooden props to keep them from falling down completely. Those buildings that have not been renovated or repaired are grey from lack of paint.

ECONOMIES

Tourism, oil, sugar, tobacco, rum and other commodities keep Cuba afloat economically.

Everyone in Cuba gets a basic amount of food at a subsidized price each week, a tour guide explained. If farmers produce extra food they can sell it to supplement their income.

The guide wouldn’t answer when I asked him what specific shortages exist in Cuba, so I am left with an unclear picture of the socio-economic situation. It is very difficult to get answers to questions in Havana.

A man on a back street in Havana Centro was selling guavas and asked if I wanted to buy any. He said they cost 2 … but two what? … I forked over 2 pesos and he started loading me up with more guavas than I could carry. Finally, I told him to stop. I gave him a pencil. As I walked away he blew a kiss at me. I later gave most of the guavas–which I don’t much like–away to people on the street who were thrilled to receive them.

There are two economies in Cuba. One is the tourist economy and the other is the local economy.

Foreigners must use Cuban convertible pesos, and locals use regular (nonconvertible) pesos. The convertible peso is the equivalent of 24 local pesos. According to the tour guide, a Cuban makes about 240 regular pesos a month (other sources indicate that salaries range from 100 to 240 pesos a month, but the government plans to institute a new 240-peso minimum wage in May 2006). That is equivalent to 24 convertible pesos, or less than a dollar a day.

The convertible peso costs $1.29 and US$1.20.

The U.S. dollar is no longer used as currency in Cuba. Until a couple of years ago it was also used alongside the regular peso and the convertible peso.

Prices for some things were about equivalent to what we would pay in Canada, but quite a bit less for other items.

For example, a mojito (rum, lime juice, mint, sugar and mineral water) ranged in price from about 2- to 3.50-convertible pesos. A similar drink in Toronto would cost anywhere from $6 to $15. Due to government restrictions on free-pouring alcohol a drink here would, of course, never contain the amount of alcohol in a Cuban cocktail–even if it were a double shot.

A taxi to the airport, which takes about half an hour, cost 20 pesos.

Two small scoops of ice cream at Coppelia cost 2.40 pesos. Coppelia is an ice cream parlour designed as a sort of post-revolutionary, utopian structure. However, uniformed guards direct tourists away from the architectural structure of interest to a tent. It appears it is for Cubans only.

Breaches in the 44-year-old U.S. trade embargo with Cuba and the 10-year-old Helms Burton act are evident everywhere.

One can easily find Marlboro cigarettes made in Switzerland, Coke and Sprite made in Mexico and watch Hollywood films. Other big corporate names in Cuba include Benetton, Nike, Reebok, Nestle, Lucky Strike and Pall Mall.

Statistics vary, but according to U.S. Department of Commerce figures, American exports to Cuba rose 5,000 percent to US$361 million in 2005 from US$7 million in 2000. Research reveals that the United States is the third largest exporter to Cuba after Spain and Venezuela and before China and Canada.

American cigarettes cost between 2 and 2.50 pesos, and Cuban cigarettes cost between .35 and 1.80 pesos.

GETTING AROUND

Tourists who don’t haggle pay five convertible pesos to go most places by taxi.

In general, Havana roads have no delineated lanes and are jammed with a jumble of cars. Most vehicles are dilapidated Soviet Ladas and old American cars apparently abandoned by their owners after the 1959 revolution.

Drivers honk their horns indiscriminately adding to the general din in Havana.

The Ladas and U.S. cars have often been painted by bristle brush in bright colours, which gives them an unusual texture. The Chevy Bel Air taxi in which I was a passenger had a floor made of painted plywood.

One of the first things you notice when you start going about in Havana is the lack of springs in seating—especially in cars, hotel chesterfields and easy chairs.

There are also ingenious little two-passenger-maximum “Coco” taxis.

The coco cabs are made of rounded Fiberglas shells built on three-wheel motorcycles. There is a seat for the driver and two seats behind for the passengers. They are incredibly unsafe by Western standards, but also the most exciting way to get around Havana as they put you right in the midst of the chaos on the roads.

The Fiberglas body of the coco cab serves as a “protective” shell around the passengers. Coco cabs are painted bright yellow, orange, green and black. Often they have painted grills on the front and other quirky markings on them to give them individual character.

Many cabbies operate horse and cart taxis or ferry people about on the backs of three-wheel and three-seat bicycle cabs.

Newer state-run cabs called “Taxi OK” seemed to be mainly Hyundai cars–either sedans or small station wagons.

There aren’t many new vehicles on the roads, but I did see Volkswagens and one Mercedes parked outside the Hotel Nacional (which serves excellent 3-peso mojitos on a patio overlooking the sea, is designated a national monument and was built in 1930).

People also travel in regular western-style city buses and elongated bus bodies hauled by truck trailer cabs.

POLITICS AND THE U.S.

The road along the Malecon (sea wall and walkway) from old Havana winds its way past the U.S. Mission from which the Americans were broadcasting visual political messages to antagonize the Cubans in January.

The Cuban government has now completely blocked the view of the façade of the Mission by erecting rows of black flags–each one with a white star in the centre–between the building and Old Havana.

In front of the flags is Plaza Anti-Imperialista where rallies are held.

Giant billboards outside the U.S. Mission resembling movie ads decry U.S. President George W. Bush. One image depicts him as a vampire with fangs and drooling blood–the mock title, “The Assassin,” is written across the top in Spanish.

Another billboard shows the face of Bush, a plus sign, the face of Adolf Hitler, an equal sign and the face of Cuban exile leader and former CIA operative Luis Posada Carriles (In other words, Bush + Hitler = Posada.).

Despite the public display of enmity, CNN is available on most restaurant television sets in Old Havana.

POLITICAL RALLYING GROUNDS

Plaza de la Revolucion is an enormous unremarkable tarmac square resembling a parking lot. There is a memorial to Che Guevara made of iron on the wall of a building on one side of the square. It is a rendering of the infamous portrait of Che wearing his beret.

Directly opposite the Che memorial is the Jose Marti Tower, which gives (for 5 pesos) great views of Havana. A museum tells the story of Marti’s life and a gallery exhibits many painted portraits of him by different artists. At the base of the tower there is a massive outdoor sculpture of Marti.

I fell down the steps in the museum in front of a group of about 20 Venezuelan military officers and scuttled out of the building in embarrassment. I was wearing sunglasses and–tourist-like–was not paying attention to what I was doing, but gawking mindlessly about.

Some of the Venezuelans had posed for photographs in front of the portraits of Jose Marti.

DINING OUT IN HAVANA

Food prices vary wildly in Old Havana restaurants. It is possible to get toast and butter for 1 peso, a vegetarian sandwich for 2.50, or a seafood platter for (at least) two people for 20. In other words, it’s easy to eat in almost any restaurant for the amount you feel like spending.

I encountered a major rip off at the Hotel Telegrafo (off of Parque Centrale, which is on the western edge of Old Havana) when the waiter kept asking me if I wanted certain food items to accompany an order of grilled shrimp and didn’t tell me there was an extra 2-peso charge for each item.

I ended up paying 18 pesos for something that should have cost no more than 8 pesos.

In my experience, El Portal del Santo Angel has the friendliest and best service in old Havana. It also has the most interesting menu (in a city without food seasoning), offering up such delicacies as crab claws with honey and garlic for 2.75 pesos and smoked salmon rolls with asparagus and mango mayonnaise for 4.35 pesos. The restaurant also serves local people.

HUSTLE AND HASSLE

On patios, if one doesn’t position oneself strategically away from the street-side seating, there is a constant barrage of beggars and peddlers with which to contend.

They include people trying to convince naïve tourists to exchange Cuban coins into convertible pesos (which would mean a great financial loss to the tourist), people making efforts to sell what look like photocopied 3-peso paper bills sporting images of Che, peanut sellers, newspaper (Granma) sellers, who are annoyed if you pay the 20-centavo price printed on the front instead of the 1 peso they demand, and people asking for cash or the food on the table.

The beggars and hawkers of that ilk were by and large senior citizens, which made me wonder about provisions for the elderly in Cuba.

Younger beggars seem to be primarily jinateros or jinateras–those who vie for longer lasting, more intimate relationships with moneyed tourists.

Generally speaking, the Cuban people are friendly and speak English very well. People asking for things can drive one mad on the streets, but in the restaurants one is at least left mainly to one’s own devices by the staff and there is no pressure to leave.

One innovative hustle was the one that occurred inside the historic house on the Plaza de Catedral in Old Havana. The so-called security guards in the rooms started asking for money, although the entry fee of 2 pesos had already been paid.

An exit fee payment of 25 pesos is required at the Havana airport before going through customs. The woman I paid shortchanged me 15 pesos.

ARTS AND MUSICAL ENTERTAINMENT

Music is everywhere in Havana. Each restaurant has a house band. The groups perform mainly son music or Latin jazz and pass the hat for tips. There are also musicians on the streets.

Attending opera in Cuba was an experience in contrasts. The baroque Gran Teatro is the most magnificent theatre I’ve ever seen. It was built in the teens. It is as if time stopped there after the revolution.

The entire place smells like the world’s stinkiest, mildewiest basement. The seats are upholstered in a bright red velvet material, but slope downward on the same angle as the rake of the floor, which made for a very uncomfortable time–especially since the 10-peso Cuban opera Realengo (libretto and music by Humberto Lara)–apparently about agrarian reform–started half an hour late.

The formerly elegant velvet curtains are rotting and their decorative golden tassels have been sloppily re-sewn into place. The white marble (I think marble) ornate and detailed carvings of human figures above the stage are black with filth. The light fixtures attached to the four balconies and box seats are all missing, which means bare bulbs light the house.

There are no flush handles on the toilets in the women’s washroom. There is only one functioning tap, which has continuously running water. It is strangely reassuring that there is an attendant collecting tips for toilet paper in the barren washroom foyer. Ushers guide patrons to seats and direct them to washrooms as if everything is as it should be. There weren’t many people in attendance and most were seated close to the stage.

Apart from the fantastic singing, the production itself was disappointingly amateur.

The assistant stage manager had to come into the house to signal by hand to the stage manager in the booth to start the show. The handful of musicians in the orchestra pit was on microphone, but the singers onstage were not. There were no footlights or spotlights. There was one light set up on the deck, which cast shadows of the actors against a stained painted backdrop of a rural house.

It is those aspects of the Havana experience that add to the sense of being in a post-apocalyptic environment.

One could forgive the appalling costumes, most likely awful due to financial constraints, but the blocking of the actors was inexcusably bad. For some unknown reason most of the action was played out on an eight-inch-high riser positioned at centre stage.

A fabulous performance at the Hotel Nacional by one of the Buena Vista Social Club bands was well worth the 20 pesos. The 3-peso drinks in the makeshift hall were not that good, but at least there was no pressure to keep buying them.

I enjoyed the Havana Club Rum Museum, the tobacco factory and the state-run gallery of Cuban art.

A tour of the cigar factory revealed that the Cuban cigars are sealed with Canadian maple sap. Each employee is given two cigars at the end of their eight-hour workday to take home, which may explain the black-market cigar trade on the streets. In the morning, a person designated as reader broadcasts Granma to the workers over a loudspeaker system. Radio soap operas are also broadcast throughout the factory in the morning, and in the afternoons the reader reads novels to the workers.

Conditions in the factory were quite good, but I noticed the workers did not have protective footwear.

Havana Club rum is stored in Canadian whiskey barrels to enhance its flavour.

I had to buy a knapsack to carry home the beautiful jewellery, wooden and paper mache crafts I purchased. Of particular interest were the crafts combining traditional African religions with Catholicism.

Elderly women sell beautifully crocheted lace shawls, tablecloths, hats and purses on the sidewalks for ludicrously low prices.

RUM COCKTAILS

The night before departure I sampled a Cuba Libre, a daiquiri, a pina colada, a Habana especial (rum and pineapple juice), and two mojitos. I got up early the next morning and toured around the city looking at last-minute sights and sites. Darted around in a coco cab a bit.

I got my photo taken for one peso by a couple of men in front of the Capitolo, which is a replica of the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. They had an old-style camera. They took my photo, and then took a photo of the photo of me attached to a photo of the dome of the Capitolo.

Had a final pina colada on Plaza Vieja and a final mojito at the airport.

I was sweating about going through Cuban security because I was worried I’d have to unpack all my crafts for inspection. But it was all quite simple–perhaps because of the 15-peso surcharge on the exit tax.

HEMINGWAY

The sixth-floor rooftop bar at Ambos Mundo in Old Havana is a fantastic place to sip rum drinks. It has fabulous views of the city and the ocean.

It costs 2 pesos to see room 511 in which Hemingway stayed off and on for 10 years. His typewriter, clothing and some of his other possessions are kept on display in the room.

The 3-peso mojitos have a somewhat artificial flavour, but the pina coladas (same price) are great.

There is a bar in the lobby lounge, which is a great place to relax. The springs and padding are gone from the back of the couches and chairs, so it can be a bit uncomfortable without creating a makeshift pillow of some sort as a backrest.

The highlight of the trip may have been an excursion to Cojimar to see the Ernest Hemingway Memorial and the former residence of Gregorio Fuentes, the fisher in The Old Man and the Sea.

Upon arrival in Cojimar by taxi, musicians who were sitting under a tree beside an old fort began to play and sing songs. I sat on the seawall and listened to them while looking at the bronze head of Hemingway who, in turn, was observing the sea surrounded by a circle of white classical columns.

I gave each band member a peso. The woman singer asked for shampoo. I didn’t have any so I gave her some soap leaves. I am sure she had no idea what to do with soap leaves so I gave her two tubes of lipstick, three pencils and three erasers. The band members blew me kisses as I left.

Punctuated the trip with a can of beer when I got home ~

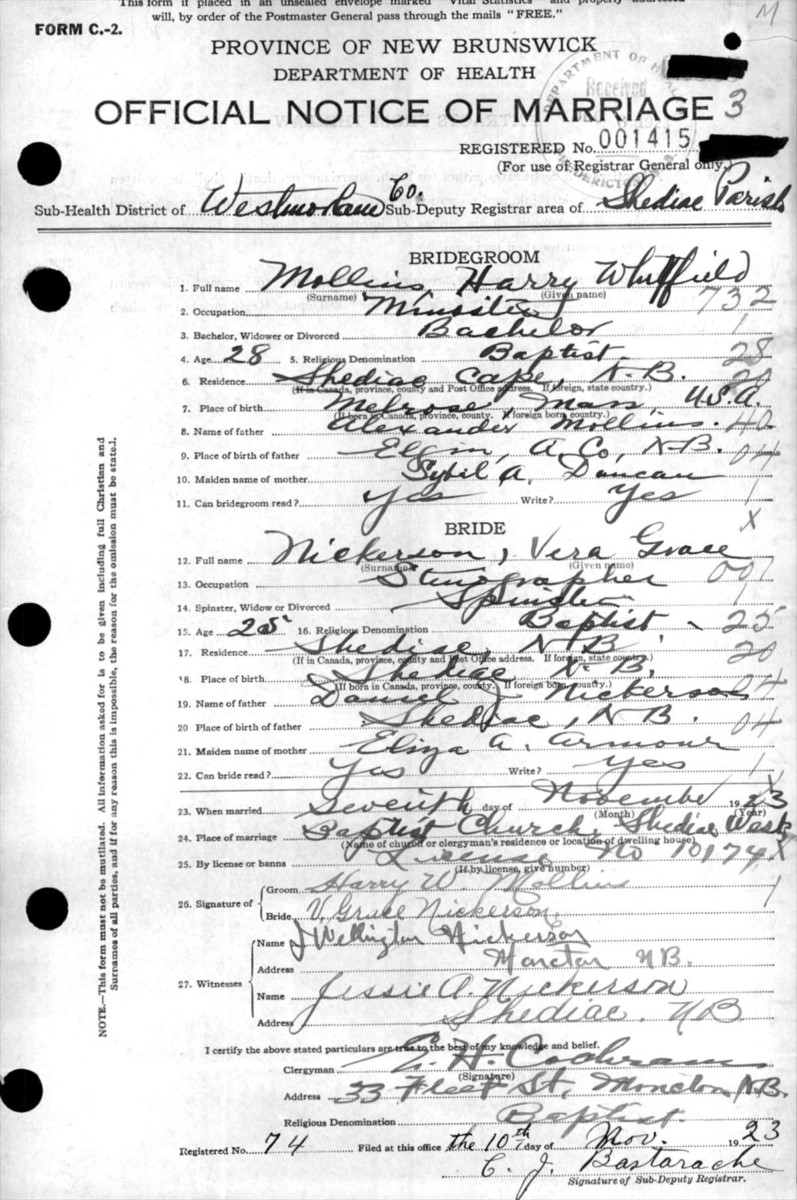

He was a Baptist minister and they moved around: from North River United Baptist Church in Westmoreland County, New Brunswick; to United Baptist Church in Windsor, Nova Scotia; to Fourth Avenue Baptist Church in Ottawa; to Park Avenue Baptist Church in Brantford, Ontario; and finally to College Street Baptist Church in Toronto.

He was a Baptist minister and they moved around: from North River United Baptist Church in Westmoreland County, New Brunswick; to United Baptist Church in Windsor, Nova Scotia; to Fourth Avenue Baptist Church in Ottawa; to Park Avenue Baptist Church in Brantford, Ontario; and finally to College Street Baptist Church in Toronto.