My sister Tracey upholds the annual festive Canada Day party our father, Carl Mollins, started hosting with my mother Joan in the 1970s.

My sister Tracey upholds the annual festive Canada Day party our father, Carl Mollins, started hosting with my mother Joan in the 1970s.

My father is missing the opportunity to celebrate “Canada 150,” the sesquicentennial of confederation in Canada on July 1, 2017, due to his untimely death at age 84 on May 28, 2016.

He would have undoubtedly found a special way to mark the anniversary of the 1967 creation of the Dominion of Canada, forged from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and the two new provinces at the time, Ontario and Quebec.

His love of Canada led to many themed art and craft collections, including sculpture, masks and images made by Indigenous peoples. He had a keen interest in artistic representations that glorified wars fought on North American soil by British, French and Indigenous people, images that through a contemporary lens represent the roots of discord that have continued to plague Canada in modern times.

He collected 18th and 19th century engravings based on romanticized history paintings depicting British war heroes dying on picturesque bloodless battlefields, equating heroic death to Christian martyrdom. Red-coated generals evoke notions of chivalry and honor, appearing as gentlemen in death throes, perhaps only tangentially engaged in courteous battle. Indigenous people are represented — or misrepresented — in the tableau images too, regardless of whether or not they were participants in the specific battle depicted.

Throughout his life and in many of the stories he wrote for Canadian readers during the 50 years he was a working journalist, my father tried to make sense of the postcolonial political frictions resulting from the dispossession of Indigenous people from their lands and conflict between Francophones and Anglophones.

As his professional career wound down at the start of the 21st century, he had been stationed in Ottawa, London, Toronto and Washington, D.C. working for various news outlets, including The Canadian Press (CP), Reuters, Westminster Press, the Toronto Star newspaper, Maclean’s, Canadian Business and MoneySense magazines.

His favorite engraving and perhaps the most iconic image of the period is “The Death of General Wolfe” by American artist Benjamin West (1738-1820), which idealizes the events that took place during the decisive battle of the French and Indian War (1754–1763) on the Plains of Abraham in Quebec on September 13, 1759, a date important to my father because my sister was born exactly 201 years later. Both General James Wolfe and the French general, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, died in the battle, which led to British victory. West made four different versions of the scene in oil.

My father was born in 1931 in Windsor, N.S. His militaristic middle name, Wellington, came from his maternal Uncle James Wellington Nickerson, a career soldier born in 1889 who fought in World War One for Canada. The name recalled British general, the Duke of Wellington, who defeated French general Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

After World War One, my grandfather Harry Whitfield Mollins, who served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in England and France, returned to Moncton, N.B., attended Acadia University in Wolfville, N.S. and married Vera Grace Nickerson of Shediac, N.B. in 1923. The family moved from Windsor to Ottawa to Brantford, Ont., named for Mohawk Joseph Brant who backed colonial loyalists during the American Revolutionary War and later established the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve.

In Ottawa, as a Boy Scout, my father was among the crowds that greeted King George VI as he paraded with Prime Minister Mackenzie King at Rideau Hall in 1939, an event that sparked a lifelong interest in the royal family. A picture of the occasion, depicting King George and the prime minister as they passed my father and his parents, seen by chance in a photographer’s shop window by a neighbour and purchased by his parents, was a prized possession.

The family lived in Brantford from 1939 to 1945 during World War Two, Harry serving as minister of Park Baptist Church — his first sermon delivered at 11 a.m. on Sept. 3, five hours after King George declared war on Germany at 11:15 a.m. in Britain. My father often remarked that due to growing up in wartime he expected to become a soldier and felt guilty as a teenager that he was not already at the front, doing his part for king and country.

In the 1970s, while working for the CP Ottawa bureau, in addition to covering the opening of King’s controversial diaries to public scrutiny, his beat included Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, national politics dominated by the Quebec separatist movement and constitutional changes that transformed Canada into a sovereign nation. During this period, the Trudeau government abandoned assimilation policies that had been devised to divest First Nations of their cultural heritage.

(L-R) Carl Mollins, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Trudeau’s press secretary Pierre O’Neil, west door, Centre Block, Parliament Buildings, Ottawa, 1974. Photographer unknown.

Subsequently, in 1984, during a four-year assignment in Washington, D.C., my father wrote a story about Francophone news media being excluded from a dinner for Prime Minister Brian Mulroney at the Canadian Embassy. At the time, Mulroney was leader of the opposition Progressive Conservative Party.

Tipped off by Mulroney’s spokesperson Bill Fox, my father wrote about how French and print media were excluded from the event and that only Anglophone television journalists were invited by the Canadian Ambassador to the United States, Allan Gotlieb.

The controversial story got good play, splashing across Canadian newspapers and making front-page news in Quebec. Gotlieb was forced to apologize to the media in the political kerfuffle that ensued.

The day the story broke, my mother Joan opened the door at about 7 a.m. to a furious Fox pounding on the door and refused to let him speak to my father who was sleeping. “You tell Carl I’m looking for him,” Fox roared at her in anger. In subsequent debates among journalists in our home about the story, my father remained firm about the importance of publicizing the injustice.

He was a keen collector, spending hours in old print shops with my mother in Washington’s Georgetown neighborhood and on London’s Charing Cross Road. When he came across a painting or an image of an engraving he did not have, he photographed it and had it framed. At the time of his death, the collection consisted of 29 framed images.

A collection of books, magazines and facts about 18th and 19th century wars in Canada gradually grew as well, culminating in a 2009 story on Reuters titled “The art of the dying general at 250 years old” marking the anniversary of England’s seizure of Quebec from France.

After my father officially retired as executive editor from Maclean’s magazine, he was asked to stay on and author a book. Titled “Canada’s Century: an Illustrated History of the People and Events that Shaped Our Identity,” the book was published in 1999 to mark the millennial in 2000. Maclean’s editor Robert Lewis asked him what job title he would like to have on the magazine masthead during that time and my father suggested “General Editor,” saying he had always wanted to be a general.

When my father finally did retire, he went on daily walks around Toronto visiting various favorite places where he would drop in for coffee, developing friendships with servers and staff at such restaurants as Against the Grain, Café Milano and Mr. Souvlaki on the lakeshore.

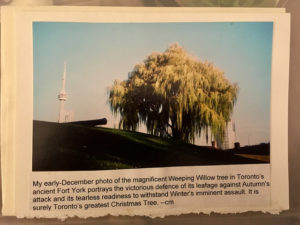

His walks included the military history site at Old Fort York where he spent many hours, one year featuring the big willow tree on the grounds on the annual Christmas card he distributed to friends and family. To mark the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812, he labored for hours over the cards, retelling the story of Laura Secord, who warned the British of an impending American attack at Queenston Heights in Niagara.

Three years later in 2015, he published his father’s diaries to mark the 100th anniversary of Harry’s enlistment in the World War One Canadian Expeditionary Force. The diaries recount his experiences in England and France.

He also liked to walk to the monument marking the site of Fort Rouille in the grounds of the Canadian National Exhibition. The fort was abandoned by the French in 1759. He would often have a cappuccino at the nearby Revival restaurant, and then walk down to the lake to the Victory Peace Monument at Coronation Park.

Most unfortunately, my father died in hospital following a tragic fall into an elevator shaft on the Pier 27 construction site on Queen’s Quay by Lake Ontario. The site and elevator did not have properly constructed protective barriers around them and four construction companies have been charged under the Ontario Occupational Health and Safety Act.

Sadly, he died peacefully 11 days afterwards in the city he loved, surrounded by me, my sister Tracey, cousin Kellie and nurses at St Michael’s Hospital. He received visits from several dear friends before he died. Despite the horrific circumstances, we think we managed to capture the sacrifice and dignity of death depicted in the dying general engravings.

At the time of his death I was living in Mexico. The last day I walked with my father and sister was on March 28, 2016. We went to Old Fort York, which was constructed in 1793 under the direction of John Graves Simcoe, lieutenant-governor of the British province of Upper Canada, and fortified early in the 19th century. Toronto (York at the time) was attacked by the U.S. Army and Navy and defended by British, Canadians, Mississaugas and Ojibways during a key battle in 1913.

We visited the Fort York canteen for coffee and a piece of cake where he chatted briefly with the staff. We then sat outside on a picnic bench marveling at our surroundings and the growth of the city, which got its start in the area.

We recently donated the military engravings and many of his other prints depicting literary and newsworthy figures to Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto, where he was a member for many years.

Story describing the image of Carl Mollins and PM Pierre Trudeau:

Wonderfully written memories. Thank you Julie.

I really liked it too. Nice chronology. I cried. Blessings to you all xx

This is really beautiful Julie.